I did not know my maternal grandmother well. Come to think of it, I did not know any of my grandparents well. Both my grandfathers died when I was young, and language barriers kept me from conversing with my paternal grandmother, even though she was present throughout most of my life.

I did not know my maternal grandmother well. Come to think of it, I did not know any of my grandparents well. Both my grandfathers died when I was young, and language barriers kept me from conversing with my paternal grandmother, even though she was present throughout most of my life.

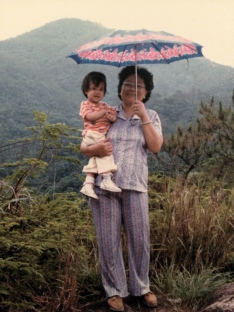

My mother’s mother, Poh Poh as I would call her, came into my life in the early 90s. She followed the path set by my two uncles as they both brought their families to Canada from Hong Kong. Until that point, I had no relationship with Poh Poh, and not much of one there after.

Again, language barriers did not help. I with my broken Cantonese could barely string together a sentence and she could hardly speak a word of English. But language was not the sole barrier. She treated my brothers and I like someone else’s family. We did not belong to her because we did not come from her sons. We came from her eldest daughter.

I knew and accepted that implicit rejection. I did not mind because I never needed her approval. She was Poh Poh; an eccentric old woman who loved Mah Jong, who at times drove people crazy, but was kind in heart and strong in will.

It was not until her recent death that I began to consider the spiritual and emotional impact of my grandmother. On the surface it would seem that there would not be much of one. She came from rural China. Patriarchy, ancestral worship, superstition were all parts and parcels of being Chinese. These were elements that influenced my upbringing but were eventually erased from my identity as I embraced a western Christ. I was so different from her, so foreign. There was no relatedness other than through blood.

But as I watched my mother struggle with her mother’s approval and acceptance, I realized that I have been carrying the same burden. We long for our mother’s embrace; we long to identify with the one who has shaped our meaning of what it means to be a woman. We long to stand in line with our foremothers who have endured tremendous hardship, suffered deep losses, and triumphed in creating beauty in midst of tragedy.

So I began to listen for my grandmother’s story and try to patch together what I knew of her and what I could understand. I used to feel disdain for her apparent ignorance and blatant favoritism towards male family members. But she was a product of her environment and so am I. Despite the differences, I began to appreciate her story and now I marvel at the distance between hers and mine. I have become so much because of the opportunities I have had here in North America. But if it were not for my grandmother, my mother would not be who she is. And if it were not for my mother, I would not be who I am.

A friend who is pregnant with her second child (a girl), shared with me that the baby is now just past the point where she has developed all the eggs she will ever have. Therefore, my friend is also carrying her possible future grandchildren. This thought floored me. It meant that at one point in my pre-history, I was in my grandmother’s womb.

Though biologically life seems to pass down through generations, spiritually the pattern is reversed. I was the first to become a follower of Christ, my mother second, and at last my grandmother who made a confession of faith on her deathbed. This is God’s redemptive power mysteriously at work and which continues to surprise me with hope. Hope that one day I will see my grandmother’s face again. Hope that I will see her and I will know her, and she will know me. Those feelings of foreignness and distance will finally be erased by the common bond of God’s love and friendship. And without any need for more words, we will be embraced.

This was a contribution to Asian American Women on Leadership, a gathering of Asian American Women for leadership renewal and development.